VERTEBRA ANATOMY

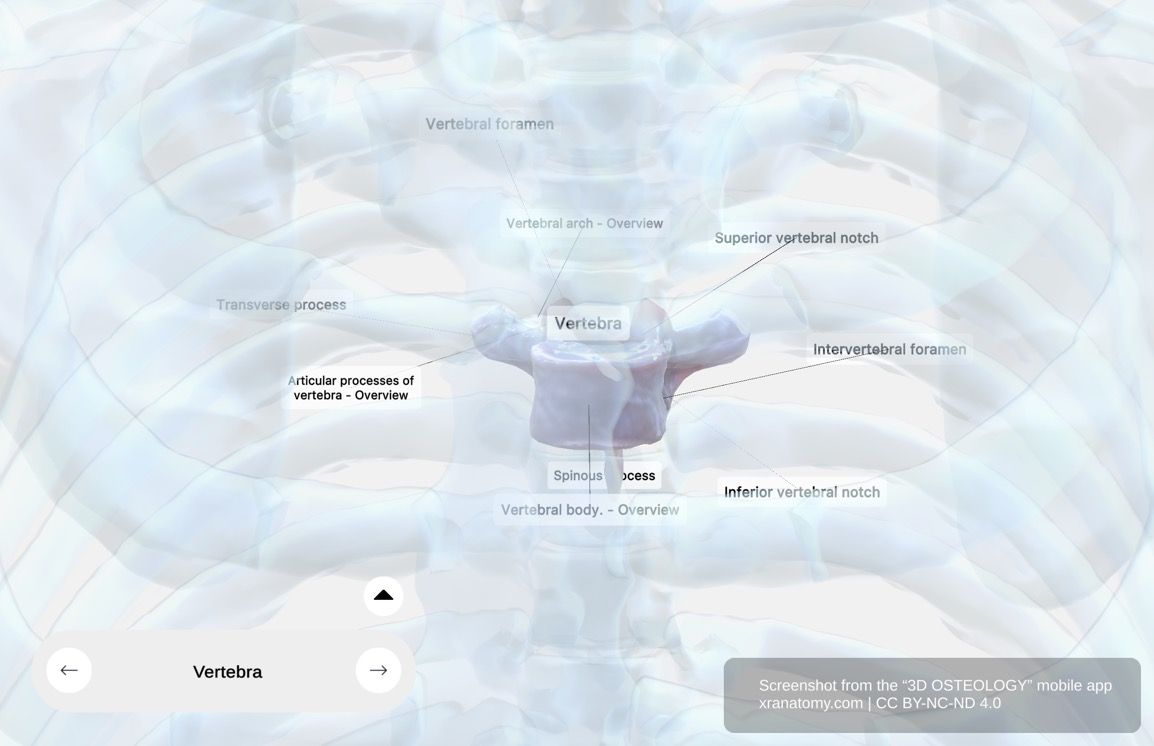

Vertebra - General Structure, Preview from the app. Download 3D OSTEOLOGY for full 3D control—multiple views, x-ray mode, and unlimited zoom.

WHY THIS MATTERS

Each vertebra is the building block of your spine. Understanding its body, arch, foramen, and processes helps you see how individual bones work together to bear your body weight, protect your spinal cord, and enable movement.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Vertebrae are individual bones that stack to form your spine. They provide structural support, protect your spinal cord, and enable movement in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. In the sacrum and coccyx, vertebrae fuse to form stationary bones. Each vertebra consists of a body, an arch, and multiple processes.

INTERVERTEBRAL FORAMEN

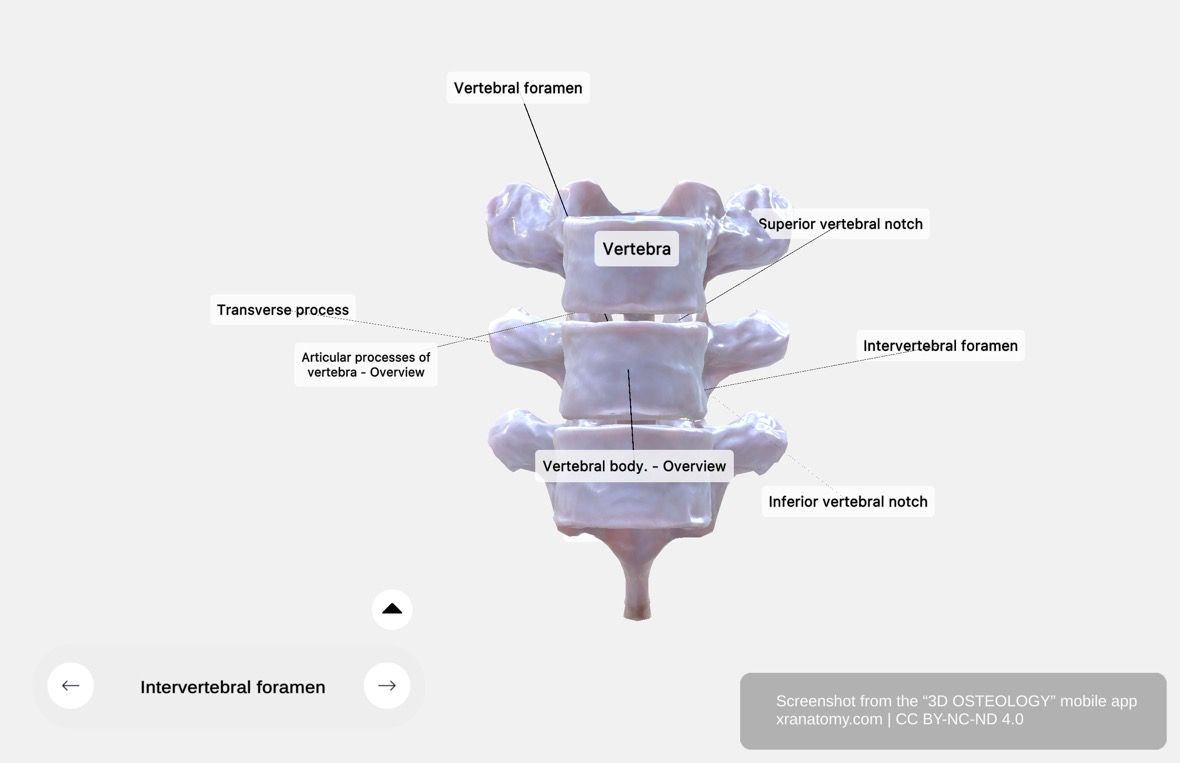

Intervertebral Foramen, Preview from the app. Download 3D OSTEOLOGY for full 3D control—multiple views, x-ray mode, and unlimited zoom.

The intervertebral foramen is an opening between adjacent vertebrae. It is formed by the alignment of superior and inferior vertebral notches. This opening allows spinal nerves to pass through, connecting your spinal cord to your body.

Superior Vertebral Notch

The superior vertebral notch is an indentation in the pedicle. It aligns with the inferior notch of the adjacent vertebra to form the intervertebral foramen.

Inferior Vertebral Notch

The inferior vertebral notch is an indentation in the pedicle. It aligns with the superior notch of the adjacent vertebra to form the intervertebral foramen.

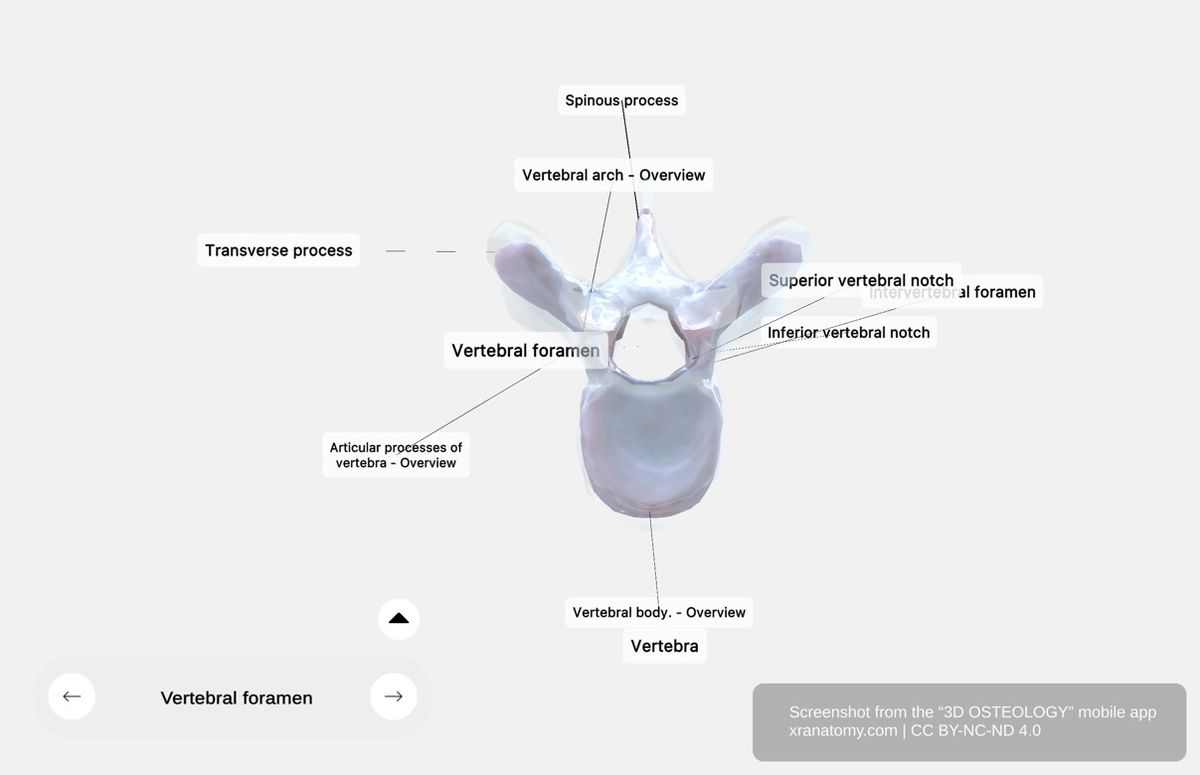

VERTEBRAL FORAMEN AND PROCESSES

Vertebral Foramen and Processes, Preview from the app. Download 3D OSTEOLOGY for full 3D control—multiple views, x-ray mode, and unlimited zoom.

Each vertebra features a central opening called the vertebral foramen, which protects your spinal cord and forms part of the vertebral canal. Surrounding it are several bony projections: the spinous process extending posteriorly, the transverse processes projecting laterally, and the articular processes (both superior and inferior) connecting adjacent vertebrae.

Vertebral Foramen

The vertebral foramen is the large central opening within each vertebra. It accommodates and protects your spinal cord and forms part of the vertebral canal.

Spinous Process

The spinous process is a bony projection extending backward from the junction of the laminae. It is visible from the posterior aspect and serves as an attachment point for your muscles and ligaments.

Transverse Process

The transverse process is a lateral projection extending from the junction of the pedicle and lamina. It is visible from the side of the vertebra. The transverse process provides attachment points for your muscles and ligaments and supports vertebral movement and stability.

Articular Processes

Each vertebra has two superior and two inferior articular processes. These allow controlled movement between your vertebrae and provide stability to your vertebral column.

Superior Articular Process

The superior articular process is an upward-facing joint surface located posteriorly on the vertebra. Its superior articular facet is the smooth, flat surface of the superior articular process.

Inferior Articular Process

The inferior articular process is a downward-facing joint surface located on the posterior part of the vertebra. Its inferior articular facet (Facies articularis caudalis) is the smooth, flat surface of the inferior articular process.

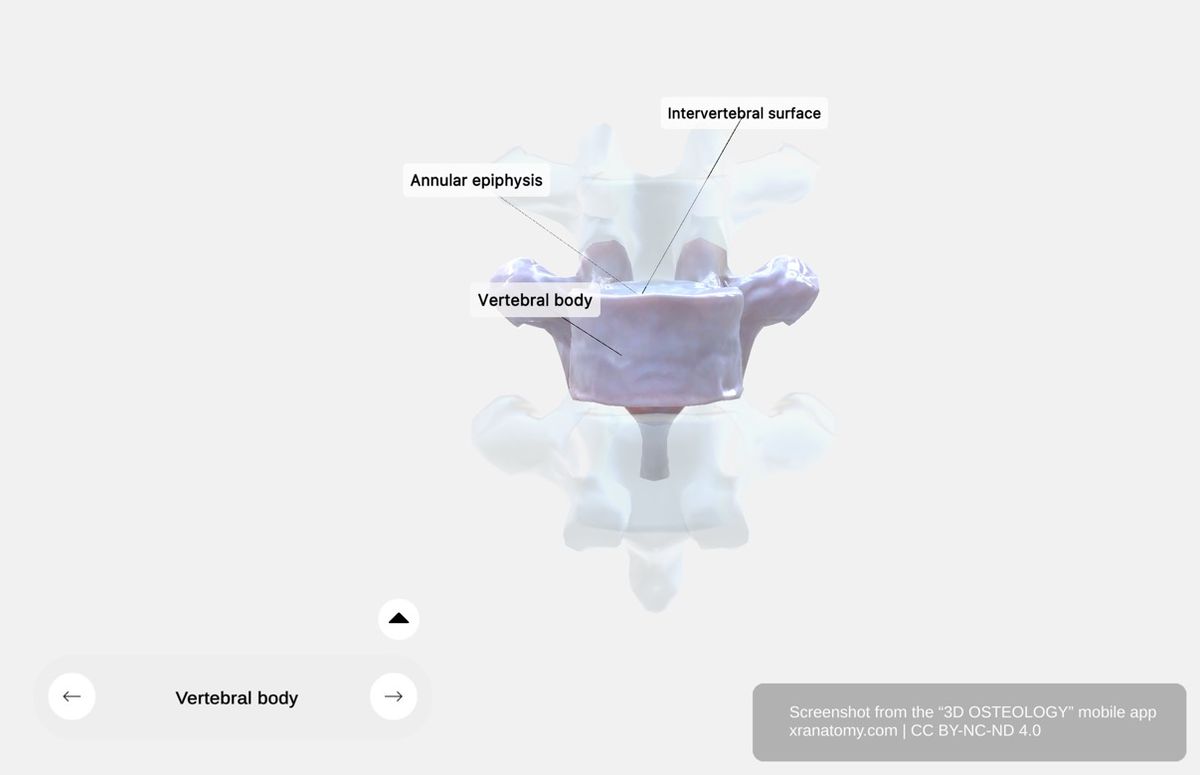

VERTEBRAL BODY

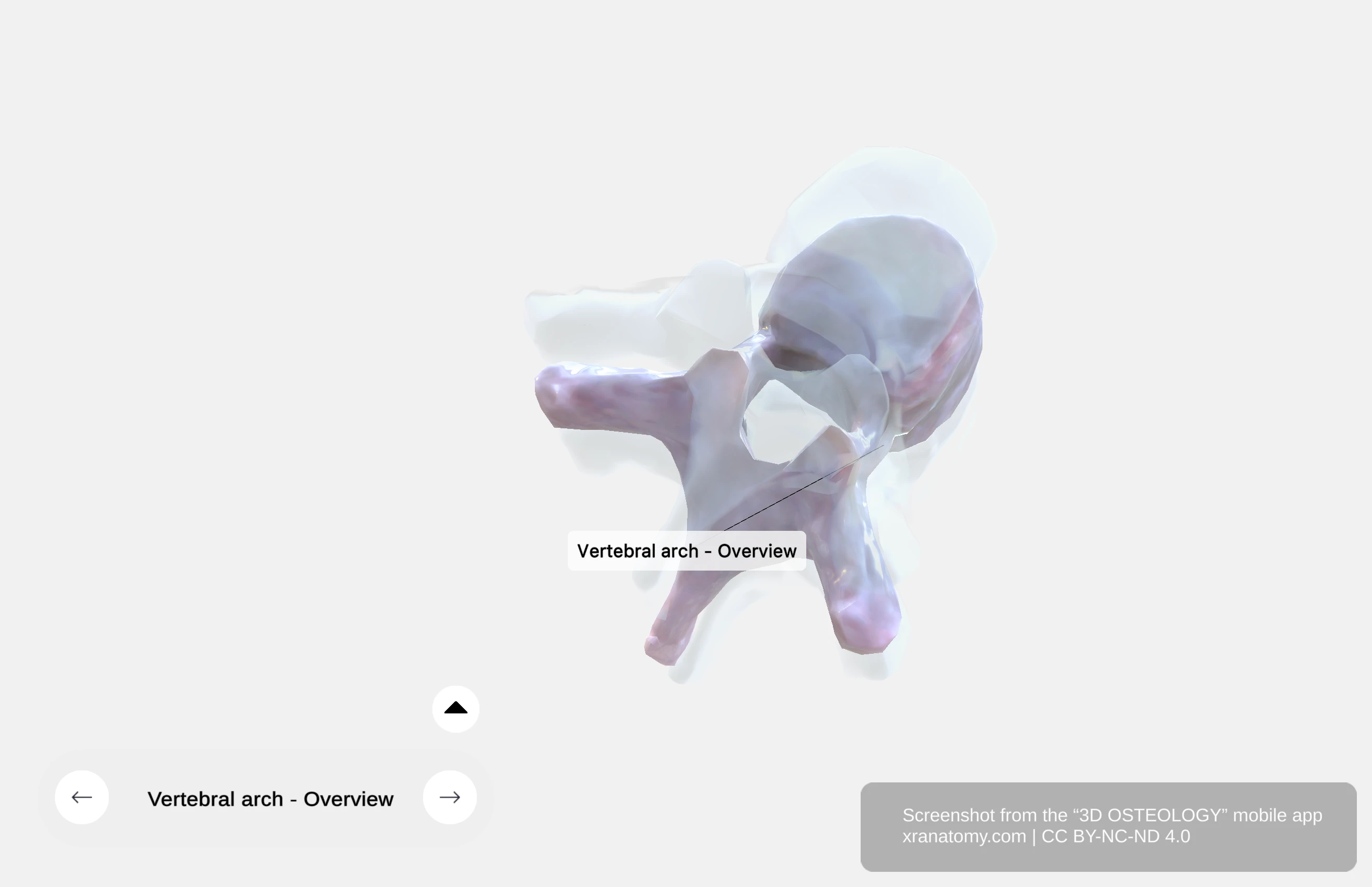

Vertebral Body and Arch, Preview from the app. Download 3D OSTEOLOGY for full 3D control—multiple views, x-ray mode, and unlimited zoom.

The vertebral body forms the anterior, weight-bearing portion of most vertebrae. It increases in size from the cervical to lumbar regions to accommodate greater loads. The vertebral body ensures proper support and distribution of your body weight. It provides support for your vertebral column and connects with intervertebral discs to absorb mechanical stress. Its key features include the intervertebral surface for disc attachment and the annular epiphysis around its margins.

Intervertebral Surface

The intervertebral surface consists of the flattened upper and lower surfaces of the vertebral body. It interfaces directly with adjacent vertebrae and provides attachment for intervertebral discs. The intervertebral surface supports stability and flexibility of your spine.

Annular Epiphysis

The annular epiphysis is a ring-like structure around the margins of the vertebral body on the top and bottom surfaces. It connects vertebrae to intervertebral discs and supports the overall structure of your vertebral column.

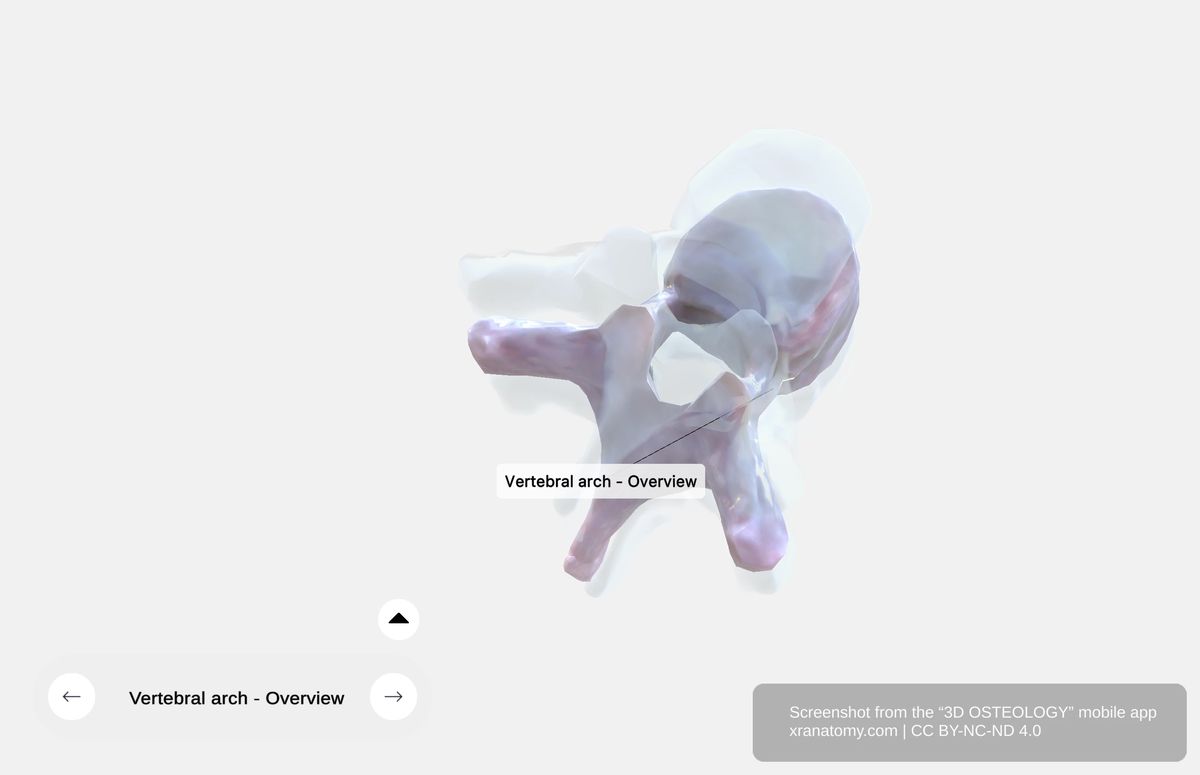

VERTEBRAL ARCH

The vertebral arch forms the posterior part of the vertebra. It surrounds and protects your spinal cord. The arch consists of two main components: the pedicles and laminae. It also serves as an attachment point for your articular processes (connecting adjacent vertebrae) and transverse processes (for muscle and ligament attachment).

Pedicles

The pedicles are short, thick projections that connect the vertebral body to the vertebral arch. They are referred to as the roots of the vertebral arch. The pedicles extend backward from the vertebral body at the junctions of its lateral and posterior surfaces.

Laminae

The laminae are the flat or arched portions of the vertebral arch. They connect the transverse processes to the spinous process and form the posterior boundary of the vertebral foramen.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING

1. Name the three main parts of a vertebra.

Reveal Answer

Body, arch, and processes.

2. What is the difference between the vertebral foramen and the intervertebral foramen?

Reveal Answer

The vertebral foramen is the large central opening within each vertebra that protects your spinal cord and forms the vertebral canal. The intervertebral foramen is the opening between adjacent vertebrae, formed by the alignment of superior and inferior vertebral notches, which allows spinal nerves to pass through.

3. What are the two components of the vertebral arch?

Reveal Answer

The pedicles (short, thick projections connecting the body to the arch) and the laminae (flat or arched portions connecting the transverse processes to the spinous process).

WHAT'S NEXT

Now that you understand the general structure of a vertebra, the next page focuses on the Atlas (C1). You will explore the first cervical vertebra, a unique ring-like structure that lacks both a vertebral body and spinous process and supports the weight of your head.

Review this page again in 3 days to reinforce what you have learned.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Henry G, Warren HL. Osteology. In: Anatomy of the Human Body. 20th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1918. p. 129–97.

2. Standring S, editor. Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier; 2016.

3. Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Essential Clinical Anatomy. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.